Micro-Review: Lymphoma in Dogs

Biomarker Expression Patterns Posters

s

Canine lymphoma is among the most frequently diagnosed type of neoplasia in dogs with incidence rates of 13–114 observed per 100,000 dogs (Teske 1994; Dobson et al. 2002). As a malignancy, it is comparable to non-Hodgkin lymphoma (NHL) in humans in many respects. The rise in incidence in humans has been mirrored in dogs, and it has been suggested that common environmental risks are responsible. Furthermore, similarities in clinical picture, molecular biology, treatment, and outcomes, and finally availability of genetic data combined with the high therapeutic treatment rates of dogs have led to the proposal that dogs are a promising spontaneous large-animal model for human NHL (Pastor et al. 2009).

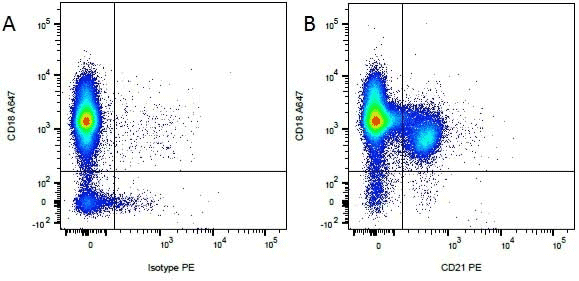

Staining canine B cells. Mouse Anti-Canine CD18 (MCA1780A647) and RPE conjugated Mouse Anti Canine-CD21 (MCA1781PE) used to stain for leukocytes and peripheral B cells. Data acquired on the ZE5 Cell Analyzer.

Susceptibility

Breed, age, and size all have an influence on susceptibility. Larger dog breeds have an increased risk of developing lymphomas with the boxer, bulldog, and bull mastiff all having a high incidence of lymphoma (Edwards et al. 2003). Additionally, some breeds have a skewing in the immunophenotype of the lymphoma, for example T or B cell derived. The T cell based lymphoma has a direct genetic association, whereas the B lymphoma is associated with combinations of risk factors (Modiano et al. 2005).

Types of Lymphoma

Multicentric lymphoma

Multicentric lymphoma represents about 75% of all lymphoma cases; these are about 65% B cell based. They are classified according to the World Health Organization’s (WHO) five stages. The most common are lymphadenopathy (stage III) with metastasis of liver and/or spleen (stage IV) or blood and/or bone marrow (stage V). Lymphomas limited to a single lymph node (stage I) or spread to some secondary lymph nodes nearby (stage II) is seen less often (Ponce et al. 2010, Vezzali et al. 2010).

Mediastinal lymphoma

The thymic or cranial mediastinal lymphoma is nearly always T cell based (Fournel-Fleury et al. 2002, Lana et al. 2006). Clinical symptoms include polyuria/polydipisia, dyspnea, or the distinctive (cranial) vena cava syndrome. The latter showing head and neck edema, due to a large mediastinal mass that restricts venous return flow to the heart.

Gastrointestinal lymphoma

Gastrointestinal lymphoma is generally T cell derived with only some showing a B cell origin (Coyle and Steinberg 2004). It can be localized to the stomach, small intestine, large intestine, as well as multiples of these sites (Frank et al. 2007).

Cutaneous lymphoma

The cutaneous lymphoma is generally a T cell lymphoma and more often epitheliotropic than non-epitheliotropic, presenting as three forms: mycosis fungoides, Sézary syndrome, and pagetoid reticulosis. Cutaneous epitheliotropic lymphoma typically manifests itself as a chronic multifocal skin disease, which can also spread to the mucous membranes and mucocutaneus junctions (Moore et al. 2009).

Pulmonary lymphoma

Involvement of the lungs is common in lymphoma whether as a primary disease, or as a result of secondary symptoms of other lymphoma (Yohn et al. 1994). Pulmonary lymphoma can develop into in bronchial, alveolar, and/or interstitial infiltrates and lymphadenopathy (Geyer et al. 2010).

Rare lymphoma

Further types of lymphoma are encountered in dogs, but these are rare. They are hepatic lymphoma (Dank et al. 2011, Keller et al. 2013), nervous system lymphoma (Veraa et al. 2010), and ocular lymphoma (Massa et al. 2002).

Diagnosis

Thoracic and abdominal radiographs together with ultrasonography of the abdomen and peripheral lymph nodes are standard techniques for the diagnosis of lymphoma. This is supplemented with cytological examination of, for example, a fine-needle aspirate from a neoplastic lymph node. While this is a quick and minimally invasive technique for diagnosing high-grade lymphoma, it may not be sensitive enough for low grade lymphoma. Here flow cytometry of fine-needle aspirates from neoplastic lymph nodes can provide the required sensitivity (Gelain et al. 2008, Comazzi and Gelain 2011). The preferred antibodies for the flow cytometric analysis of lymphomas include CD21, CD79α, and PAX5 for B-cell lymphoma and CD3, CD4, and CD8 for T-cell lymphomas (Caniatti et al. 1996).

Discover an industry leading portfolio of canine-specific antibodies for flow cytometric analysis in our online catalog. Validated antibodies with decades of peer reviewed use in scientific journals are available in several formats to enable multicolor flow cytometry staining.

References:

- Caniatti M et al. (1996). Canine lymphoma: immunocytochemical analysis of fine-needle aspiration biopsy. Vet Pathol. 33(2), 204-212.

- Comazzi S and Gelain ME (2011). Use of flow cytometric immunophenotyping to refine the cytological diagnosis of canine lymphoma. Vet J. 188, 149–155.

- Coyle KA and Steinberg H (2004). Characterization of lymphocytes in canine gastrointestinal lymphoma. Vet Pathol. 41(2), 141-146.

- Dank G et al. (2011). Clinical characteristics, treatment, and outcome of dogs with presumed primary hepatic lymphoma: 18 cases (1992–2008). J Am Vet Med Assoc. 239, 966–971.

- Dobson JM et al. (2002). Canine neoplasia in the UK: estimates of incidence rates from a population of insured dogs. J Small Anim Pract. 43(6), 240-246.

- Edwards DS et al. (2003). Breed incidence of lymphoma in a UK population of insured dogs. Vet Comp Oncol. 1(4), 200-206.

- Fournel-Fleury C et al. (2002). Canine T-cell lymphomas: a morphological, immunological, and clinical study of 46 new cases. Vet Pathol. 39(1), 92-109.

- Frank JD et al. (2007). Clinical outcomes of 30 cases (1997-2004) of canine gastrointestinal lymphoma. J Am Anim Hosp Assoc. 43(6), 313-321.

- Gelain ME, et al. (2008). Aberrant phenotypes and quantitative antigen expression in different subtypes of canine lymphoma by flow cytometry. Vet Immunol Immunopathol. 121, 179–188.

- Geyer NE et al. (2010). Radiographic appearance of confirmed pulmonary lymphoma in cats and dogs. Vet Radiol Ultrasound. 51(4), 386-390.

- Keller SM et al. (2013). Hepatosplenic and hepatocytotropic T-cell lymphoma: two distinct types of T-cell lymphoma in dogs. Vet Pathol. 50, 281–290.

- Lana S et al. (2006). Diagnosis of mediastinal masses in dogs by flow cytometry. J Vet Intern Med. 20(5), 1161-1165.

- Massa KL, et al. (2002). Causes of uveitis in dogs: 102 cases (1989-2000). Vet Ophthalmol. 5(2), 93-98.

- Modiano JF et al. (2005). Distinct B-cell and T-cell lymphoproliferative disease prevalence among dog breeds indicates heritable risk. Cancer Res. 65(13), 5654-5661.

- Moore PF et al. (2009). Canine epitheliotropic cutaneous T-cell lymphoma: an investigation of T-cell receptor immunophenotype, lesion topography and molecular clonality. Vet Dermatol. 20(5-6), 569-576.

- Pastor M et al. (2009). Genetic and environmental risk indicators in canine non-Hodgkin's lymphomas: breed associations and geographic distribution of 608 cases diagnosed throughout France over 1 year. J Vet Intern Med. 23(2), 301-310.

- Ponce F et al. (2010). A morphological study of 608 cases of canine malignant lymphoma in France with a focus on comparative similarities between canine and human lymphoma morphology. Vet Pathol. 47(3), 414-433.

- Teske E (1994). Canine malignant lymphoma: A review and comparison with human non‐hodgkin's lymphoma. Veterinary Quarterly 16(4), 209-219.

- Vezzali E et al. (2010). Histopathologic classification of 171 cases of canine and feline non-Hodgkin lymphoma according to the WHO. Vet Comp Oncol. 8(1), 38-49.

- Veraa S, et al. (2010). Comparative imaging of spinal extradural lymphoma in a bordeaux dog. Can Vet J. 51, 519–521.

- Yohn SE et al. (1994). Confirmation of a pulmonary component of multicentric lymphosarcoma with bronchoalveolar lavage in two dogs. J Am Vet Med Assoc. 204(1), 97-101.