Popular topics

-

References

Arifuzzaman M et al. (2019). MRGPR-mediated activation of local mast cells clears cutaneous bacterial infection and protects against reinfection. Science Advances 5, eaav0216.

Bañuelos-Cabrera I et al. (2014). Role of histaminergic system in blood-brain barrier dysfunction associated with neurological disorders. Arch Med Res 45, 677-686.

Chikahisa S et al. (2013). Histamine from brain resident MAST cells promotes wakefulness and modulates behavioral states. PloS One 8, e78434.

Echtenacher B et al. (1996). Critical protective role of mast cells in a model of acute septic peritonitis. Nature 38,175-7.

Hood S and Amir S (2017). Neurodegeneration and the circadian clock. Front Aging Neurosci 9,170.

Kondo K et al. (2006). Expression of chymase-positive cells in gastric cancer and its correlation with the angiogenesis. J Surg Oncol 93, 36-42.

Ma Y et al. (2013). Dynamic mast cell-stromal cell interactions promote growth of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 73, 3927-3937.

Nautiyal KM et al. (2008). Brain mast cells link the immune system to anxiety-like behavior.PNAS 105, 18053-18057.

Secor VH et al. (2000). Mast cells are essential for early onset and severe disease in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med 191, 813-822.

Smith JH et al. (2011). Neurologic symptoms and diagnosis in adults with mast cell disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 113, 570-574.

Wedemeyer J and Galli SJ (2005). Decreased susceptibility of mast cell-deficient Kit(W)/Kit(W-v) mice to the development of 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine-induced intestinal tumors. Lab Invest 85, 388-96.

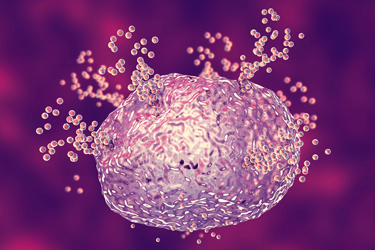

A MASTer Immune cell

The various functions of most leukocytes are well-known by immunologists, however only a few know the true functional scope that mast cells play in the body. These innate, granulated cells are too often mentioned only briefly when discussing their release of histamine, which causes many people to have itchy and puffy eyes in the spring. In reality, mast cells have diverse functions and are involved in many operations of body homeostasis, immunity, and disease. In this guest blog, we take a look at some of the areas that mast cells play a role in.

Mast Cells Outside of Allergy

An important indicator that mast cells are not just mediators of allergy came when researchers found that they were activated by substances other than allergen-bound immunoglobulin E (IgE). Over the past 50 years, mast cells have been shown to express surface receptors for a variety of complement proteins, microbial products, cytokines, chemokines, and even neuropeptides. Furthermore, depending on the stimulating factor, mast cells release specific types of proteases, lipid factors, growth factors, and pro- or anti-inflammatory cytokines.

Based on these observations, along with new methods for producing conditional knockout models and mast cell stabilization, mast cell research has greatly expanded in the past three decades. Although there are multiple areas that include mast cell research, this article will briefly touch on three areas of potential mast cell influence: infectious disease, cancer, and neurodegenerative disorders.

Mast Cells and Infections

Although mast cells are found throughout the body, they are particularly numerous in the skin and mucosal sites. While not often appreciated as such, mast cells are one of the first responders to both bacterial and viral infections at sites of host-pathogen interface, like the intestines and lungs.

Mast cells express both Toll-like receptors (TLRs) and nucleotide-binding oligomerization domain-like receptors (NLRs) that allow them to identify bacterial and viral products. While mast cells can produce some antimicrobial peptides, they release potent and far-reaching chemoattractants for neutrophils and dendritic cells to phagocytose and clear pathogens. In mast cell knockout mice, decreased clearance of bacteria in certain models of sepsis has been described (Echtenacher et al. 1996).

A recent study from Arifuzzaman et al. (2019) also suggests that stimulation of a specific mast cell mas-related G protein-coupled receptor was particularly effective in preventing reinfection of Staphylococcus aureus in mice over non-stimulated mice. Mast cell signaling was also shown to increase dendritic cell migration to the lymph nodes to boost antigen presentation. Thus, increasing mast cell activation during infections could prove to increase immunity or be therapeutically beneficial for some patients.

Mast Cells and Cancer

Although mast cells have long been described infiltrating into and around tumors, their exact role has been difficult to understand. In human studies, increased mast cell numbers around tumors strongly correlated with worse outcomes of gastric and pancreatic cancer (Kondo et al. 2006, Ma et al. 2013). One theory suggests that mast cells modulate blood flow and vascular growth around some tumors, allowing them to expand and access nutrients. Mast cells not only cause increased vascular permeability through the release of histamine, but also release vascular and endothelial growth factors, which could benefit certain types of tumors (Kondo et al. 2006).

In mast cell knockout mice, tumor progression can be halted (Wedemeyer and Galli 2005), although the use of therapeutics to deplete mast cells has shown mixed results, depending on the model, with some even worsening the outcome. Although the exact mechanism of mast cells in cancer progression remains unclear, exciting research suggests that mast cells could play a significant role in the progression of some cancers.

Mast Cells and Neurodegenerative Disorders

While mast cells are present in relatively small numbers in the brain, mouse models suggest that brain mast cells can greatly influence innate behaviors. Most mast cells are found in the diencephalon in the brain, as well as the meninges. Through mast cell knockout studies, it has been observed that mast cells help regulate the brain’s central histaminergic system, which controls circadian rhythms (Chikahisa et al. 2013). One group additionally found that blocking brain mast cell activation with a stabilizing drug, increased anxiety-like behavior in mice (Nautiyal et al. 2008).

While too few mast cells appear to negatively affect behavior, too many could trigger or exacerbate neurodegenerative disorders. In patients with multiple sclerosis or Alzheimer’s disease, it appears that increased number of mast cells are located around neurodegenerative plaques (Bañuelos-Cabrera et al. 2014, Secor et al. 2000). In mouse models of multiple sclerosis, it also appears that mast cells are necessary for induction and progression of the disease (Secor et al. 2000). Interestingly, patients with neurodegenerative disorders also experience significantly altered sleep/wake cycles even before noticeable neurological symptoms appear (Hood and Amir 2017), which may suggest that mast cells play an early role in these diseases.

Similarly, patients with mastocytosis, which increases mast cells numbers throughout the body, also experience neuropsychiatric symptoms and memory issues (Smith et al. 2011). These symptoms often diminish after the disease is managed with mast cell stabilizers.

Although there is growing evidence that mast cells can greatly influence the brain and behavior, much is still unknown.

A Cell of Possibilities

While best known for their role in allergic reactions, mast cells have more to offer than just annoying redness and swelling during the pollen season. Due to their distribution throughout the body and diverse stimulating factors, mast cells are continually being implicated in new body systems and diseases. These underappreciated cells may well be therapeutic targets in infection, cancer, neurological disorders, and beyond.

Looking for Mast Cell Markers?

Bio-Rad has a number of different markers that can be used to identify mast cells.

Learn MoreReferences

Arifuzzaman M et al. (2019). MRGPR-mediated activation of local mast cells clears cutaneous bacterial infection and protects against reinfection. Science Advances 5, eaav0216.

Bañuelos-Cabrera I et al. (2014). Role of histaminergic system in blood-brain barrier dysfunction associated with neurological disorders. Arch Med Res 45, 677-686.

Chikahisa S et al. (2013). Histamine from brain resident MAST cells promotes wakefulness and modulates behavioral states. PloS One 8, e78434.

Echtenacher B et al. (1996). Critical protective role of mast cells in a model of acute septic peritonitis. Nature 38,175-7.

Hood S and Amir S (2017). Neurodegeneration and the circadian clock. Front Aging Neurosci 9,170.

Kondo K et al. (2006). Expression of chymase-positive cells in gastric cancer and its correlation with the angiogenesis. J Surg Oncol 93, 36-42.

Ma Y et al. (2013). Dynamic mast cell-stromal cell interactions promote growth of pancreatic cancer. Cancer Res 73, 3927-3937.

Nautiyal KM et al. (2008). Brain mast cells link the immune system to anxiety-like behavior.PNAS 105, 18053-18057.

Secor VH et al. (2000). Mast cells are essential for early onset and severe disease in a murine model of multiple sclerosis. J Exp Med 191, 813-822.

Smith JH et al. (2011). Neurologic symptoms and diagnosis in adults with mast cell disease. Clin Neurol Neurosurg 113, 570-574.

Wedemeyer J and Galli SJ (2005). Decreased susceptibility of mast cell-deficient Kit(W)/Kit(W-v) mice to the development of 1, 2-dimethylhydrazine-induced intestinal tumors. Lab Invest 85, 388-96.

You may also be interested in...

View more Immunology or Guest Blog blogs