Popular topics

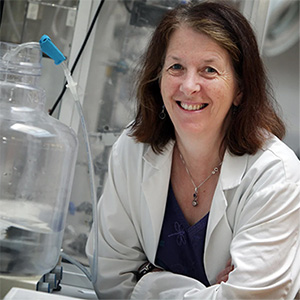

Voices of Women in Science: Associate Professor Carolyn Carr

As part of International Day of Women and Girls in Science, Bio-Rad invited researchers to share their own experiences of being a woman in science. In this article, we speak to Associate Professor Carolyn Carr about her career.

Carolyn Carr is an Associate Professor of Biomedical Science at the University of Oxford, UK. Her research focuses on using stem cells to study metabolic changes of cardiomyocytes in disorders such as diabetes. She has had an interesting and diverse career path and speaks openly of the difficulties she faced to get to the position she is in now - a career in research with her own research team.

Associate Professor Carolyn Carr. Image courtesy of Carolyn Carr.

Bio-Rad (BR): When did you first become interested in a career in science?

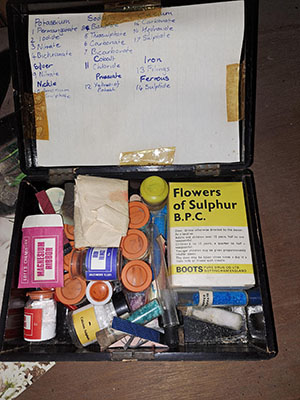

Carolyn Carr (CC): I think I always knew I wanted to work in science and that I wanted to do experiments. My grandparents were teachers of physics and botany and I had a chemistry set as a child. At school, I was better at maths than chemistry but I wanted to do chemistry at university. When I was preparing to do the University of Oxford, UK, entrance exam my chemistry teacher asked why I wasn’t applying to do maths, and I said that I couldn’t think of a job doing maths that was interesting, I wanted to work in chemistry.

BR: Can you describe your career path?

BR: Can you describe your career path?

CC: I got into Oxford and did a chemistry degree. The University of Oxford was one of the first universities to do a four year degree with a full year of research — the Part II year. I loved my Part II , where I was using nuclear magnetic resonance (NMR) spectroscopy to study the reactions between molecules. I graduated in 1981 and got a second class degree because Oxford didn’t split the seconds into 2.1 and 2.2 in those days. That wasn’t good enough to stay on and do a DPhil (the University of Oxford term for a PhD) as you needed a first. Despite being told by the University careers department that women didn’t work in research, I got a job with Kodak in Liverpool, working in the research department which made new photosensitive chemicals to form the colors in photographic film.

My job was to do mass spectrometry to find out if they had made the chemical they were aiming for. I absolutely loved it. I was the only woman in the research team but I got on well with the guys. I got married in 1982 and my husband was training to become an RAF pilot. I stayed at Kodak while he moved around the country to different training bases. In 1984 he was posted to RAF Northolt and I started to think about what I should do. I wrote to my research supervisor from my Part II and asked if there were any jobs in Oxford. He said that as I had worked in industry, I was eligible for funding to do a DPhil so I went back to the chemistry department in Oxford and again used NMR, but this time to look at the shape of molecules. In my final year, I was pregnant and made an interesting sight in a department that was still predominantly male! I passed my DPhil about 2 months before my daughter, Melanie, was born.

Being a mother and an RAF wife, moving house every 2 to 3 years, does not go well with a career in chemistry research but I found a job that I could do from home. I worked for a publishing company, Derwent Information, and wrote abstracts of new patents in chemistry. It wasn’t research but it kept my chemistry brain ticking over and brought in a bit of spending money. I did that until my husband left the RAF in 1998 and joined a commercial airline. I had tried applying for jobs once the children went to school but with no success as I had been away from the lab for over seven years. However, I learned about the Daphne Jackson Trust which funds people with a career break to get back into research.

I applied for a Daphne Jackson Trust Fellowship and was successful, so I went back to Oxford and NMR spectroscopy, this time working in a group that researched chemotherapy drugs. While I was there, one of my colleagues started working with a new spin-out company, Synaptica Ltd, which was looking for a cure for Alzheimer’s. They wanted someone to do mass spectrometry so I joined them when my fellowship finished. Sadly, the company ran out of funding after three years and so in 2003, I was looking for jobs again. I applied for a post-doc position with a group in Oxford as they wanted someone to do NMR spectroscopy in their research into heart disease. I got the job and have been there ever since. I spent some time as a post doc before forming my own research team.

BR: Have you encountered any challenges along the way and if so, how did you overcome them?

CC: I think the biggest challenge was getting back into science after my career break. I began to feel I would never get an interview, let alone a job, which was very depressing. I joined the Royal Society of Chemistry (RSC) and went to a job fair in London. I was amazed at how much spectroscopy had changed in the 11 years I had been away. It was through the RSC that I saw an advert for the Daphne Jackson Trust and that got me back to the lab.

BR: Can you tell us about your current research?

CC: My current work uses stem cells to make human heart cells to study in the lab. Unlike many other cells from the body, it is not easy to get pieces of human heart. Even if you are lucky enough to work with a cardiac surgeon, they can only let you have a tiny bit of tissue and the cells don’t survive long in vitro. Using stem cells we can make billions of human heart cells and look at how their biology changes in disease. My group has made a model of the cells in the diabetic heart and are looking at what goes wrong in those cells with the imbalance of sugar and fat in diabetes.

BR: What has been your career highlight to date?

CC: Seeing my students graduate and get successful jobs and presenting my work at international conferences.

BR: Are there any scientists who have inspired you?

CC: Not directly, but I always knew of Marie Curie and that women could do science. My supervisor for my DPhil was also a lovely man with the most amazing knowledge of chemistry.

BR: What advice would you give to women looking to pursue a career in science?

CC: Go for it, science is amazing. It is not the best paid career by far, but when it goes well you will learn things noone else knows! You need to be someone who likes solving puzzles and figuring out how to make things work because a lot of experiments don’t go the way you want, and you need to go back to the beginning and try a different route. It is worth it when they then go well, particularly if they give you the answer you were hoping for!

Interested in Hearing More Stories from Women in Science?

Our Voices of Women in Science blogs give insights into the diverse and interesting careers of researchers at different career stages.

You may also be interested in...