Popular topics

-

References

Al-Harbi KS (2012). Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adher 6, 369-88.

Border R et al. (2019). No support for historical candidate gene or candidate gene-by-interaction hypotheses for major depression across multiple large samples. Am J Psychiatry 176, 376-387.

David T et al. (1974). A selective inhibitor of serotonin uptake: Lilly 110140, 3-(p-Trifluoromethylphenoxy)-n-methyl-3-phenylpropylamine. Life Sci 15, 471-479.

Gold P et al. (2015). Clinical and biochemical manifestations of depression: relation to the neurobiology of stress. Neural Plast 2015, 1-11.

López-López et al. (2019). The process and delivery of CBT for depression in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychol Med 49, 1937-1947.

Moncrieff J et al. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry, doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Mulinari S (2012). Monoamine theories of depression: historical impact on biomedical research. J. Hist Neurosci 21, 366-392.

Northwestern University (2009). "Why antidepressants don't work for so many." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091023163346.htm

Tye KM et al. (2013). Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature 493, 537–541.

The Biochemical Basis of Depression

What Is Depression and What Causes It?

According to the World Health Organisation, around 5% of adults suffer from depression globally, and the number of people reporting mental health problems increases year on year. Depression can be a serious, debilitating, and even fatal condition, which affects every aspect of a person’s life: from underperforming at work, and losing interest in hobbies, to struggling to maintain relationships.

The causes of depression are numerous and varying; grief, traumatic or stressful life events, substance misuse, and certain genetic traits may all increase the likelihood of depression. Depression can also appear out of nowhere for some people, affecting those who feel like they shouldn't be depressed.

This blog post will outline what is currently known about depression and anti-depressants, in the context of brain biochemistry.

The Serotonin Theory

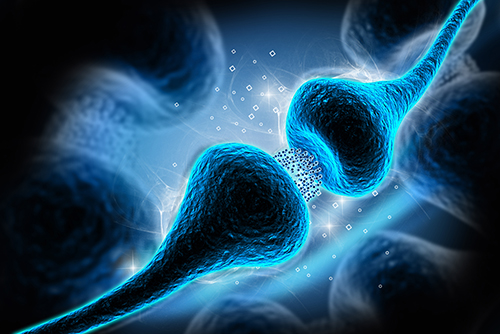

In the 1960s, the brain chemical serotonin became widely recognized as being implicated in depression (Mulinari 2012). Serotonin is a neurotransmitter: a small signaling molecule secreted by a neuron in the brain. Once secreted, it passes across a synapse to reach another neuron to relay the signal. In the case of serotonin, the signal is believed to have mood boosting effects when released and efficiently taken up by neurons in the brain. The serotonin theory of depression suggests that a decreased production of serotonin or diminished activity of serotonin pathways plays a causal role in the pathophysiology of depression.

Antidepressants

In the late 1980s, anti-depressant drugs, called serotonin selective reuptake inhibitors (SSRIs), were introduced to the market (David et al. 1974). After relaying a message in neural synapses, serotonin is reabsorbed by nerve cells. SSRIs work by blocking this reuptake of serotonin, leaving more in the synapse to continue producing mood-boosting effects (Figure 1). With the advent of SSRIs came further support for the serotonin theory. In fact, the serotonin theory and explanation of how SSRIs work is still widely subscribed to by researchers and doctors alike today.

Fig. 1. Illustration of the mechanism of action of SSRIs at a synapse. After serotonin is released from the pre-synaptic nerve, SSRI molecules inhibit its reabsorption. This leaves more serotonin in the synapse to bind to receptors on the post-synaptic nerve and relay its signal.

However, a recent comprehensive review of the major research suggested there is little evidence that low serotonin concentration or activity causes depression (Moncrieff et al. 2022). The majority of studies found no evidence of reduced serotonin activity in people with depression compared to people without the disease. Therefore, the commonly accepted mode of action for SSRIs working via serotonin reuptake inhibition is also drawn into question. It might be that they work simply by amplifying the placebo effect, or they may dampen down all emotions in general, giving a perceived decrease in certain symptoms of depression, such as low mood and irritability.

Further evidence that the serotonin theory may not be the only explanation of depression is that SSRIs, and depression medication as a whole, is not ‘one size fits all’. If a lack of serotonin was the only driver of depression, SSRIs would work for nearly all patients, yet this is not the case: 10-30% of patients have SSRI resistant depression, meaning they do not respond to SSRI treatment (Al-Harbi 2012). This suggests that the serotonin theory of depression might be oversimplified and/or outdated. A more recent study by Northwestern University, Illinois used mice models to show depression begins further up in the chain of synaptic events than serotonin release and efficacy at the synapse; they indicate that depression may begin in the development and functioning of neurons. Instead of targeting the cause of the problem, they suggest that antidepressants only treat the effect of the problem. This may be why antidepressants take many weeks or even months to begin to provide any relief to the patient.

Fortunately, SSRIs are not the only treatment available to tackle depression. One of the main alternatives is cognitive behavioural therapy (CBT). CBT is a type of talking therapy, which can help patients to identify unhelpful thinking patterns and find alternative ways to think through problems and overcome negative thoughts (López-López et al. 2019). In recent years, lots of CBT provision has moved online, making it increasingly accessible for people to get the help they need without having to travel to physical appointments.

Dopamine

While serotonin is linked with a mood balancing role in the brain, dopamine is involved in reward and ‘motivated behavior’. This includes why people take pleasure from food, sex, and drugs. Reduced ability to experience pleasure is called anhedonia and is a commonly reported symptom of depression, causing people to withdraw from hobbies and activities they would usually enjoy. One study, focusing on testing the hypothesis that dopamine is implicated in depression, used mice with halorhodopsin-containing dopamine neurons. Halorhodopsin acts to inhibit dopamine signals by a light-gated ion pump, which hyperpolarizes (or inhibits) specific neurons. The researchers used a tail suspension test, hanging mice up by their tail to look at how a lack of dopamine signaling affects motivated behavior. Wild-type mice, with functioning dopamine neurons, will struggle for a while and eventually give up after some time. In contrast, the mice with ineffective dopamine signalling gave up their struggle much faster. This experiment neatly showed a link between dopamine and anhedonia — a major symptom of depression (Tye et al. 2013).

How Depression May Physically Alter Areas of the Brain

Serotonin and other neurotransmitters in the brain have long been studied to try and elucidate the biochemical mechanism of depression. But what about other areas of the brain? Are there any structural differences between the brain of someone with depression versus the brain of someone without? Neuroimaging studies involving post-mortem brain scans of patients who had committed suicide revealed a 40% decrease in the volume of the left subgenual cortex, an area of the brain involved in regulating emotion. While degeneration in this area is associated with depression, studies have shown that cerebral blood flow and metabolic activity are increased in the amygdala of patients with depression (Gold et al. 2015). Both of these studies indicate that depression and physical change within the brain are somehow linked. What remains unclear is if the changes in the brain are a driving cause of depression or if they are a result of the disease.

Depression and Genetics

As genetic traits have also commonly been cited as a potential cause of depression, studies have been conducted to elucidate the link between particular genes and the likelihood of developing depression. While some smaller studies have shown positive findings, the same was not seen in larger and more rigorous findings (Border et al. 2019). Instead, these studies served to illustrate the importance of sample size and experimental rigor.

Conclusion

For such a ubiquitous disease, affecting millions of people worldwide, there are remarkably large gaps in our knowledge about the biochemical factors driving the condition. While widespread oversimplification of depression by researchers and medics alike may have stunted full understanding of the disease for decades, it will be exciting to see what we learn about the disease in coming years and how these insights may translate into efficacious treatments and medicine.

Interested in the Role of Neurotransmitters in the Brain?

Bio-Rad has a range of neurotransmitter, receptor, and transporter antibodies to facilitate your research.

References

Al-Harbi KS (2012). Treatment-resistant depression: therapeutic trends, challenges, and future directions. Patient Prefer Adher 6, 369-88.

Border R et al. (2019). No support for historical candidate gene or candidate gene-by-interaction hypotheses for major depression across multiple large samples. Am J Psychiatry 176, 376-387.

David T et al. (1974). A selective inhibitor of serotonin uptake: Lilly 110140, 3-(p-Trifluoromethylphenoxy)-n-methyl-3-phenylpropylamine. Life Sci 15, 471-479.

Gold P et al. (2015). Clinical and biochemical manifestations of depression: relation to the neurobiology of stress. Neural Plast 2015, 1-11.

López-López et al. (2019). The process and delivery of CBT for depression in adults: A systematic review and network meta-analysis. Psychol Med 49, 1937-1947.

Moncrieff J et al. (2022). The serotonin theory of depression: a systematic umbrella review of the evidence. Mol Psychiatry, doi.org/10.1038/s41380-022-01661-0

Mulinari S (2012). Monoamine theories of depression: historical impact on biomedical research. J. Hist Neurosci 21, 366-392.

Northwestern University (2009). "Why antidepressants don't work for so many." ScienceDaily. ScienceDaily, www.sciencedaily.com/releases/2009/10/091023163346.htm

Tye KM et al. (2013). Dopamine neurons modulate neural encoding and expression of depression-related behaviour. Nature 493, 537–541.

You may also be interested in...

View more Neuroscience or Guest Blog blogs